Dominique Mouflier, the daughter of Jacques Mouflier, tells the story so well, of all that her father has brought to Val d’Isère.

The introduction in her father’s book, ‘Naissance d’un village olympique’ (‘Birth of an Olympic village’), reflects perfectly what we want to get across. This is what it says:

“Studying the history of a small mountain village that was destined to become a world-class resort, talking about those earlier years when we had a glimpse of the dazzling future that lay ahead, seems like an act of stubborn attachment to the past.

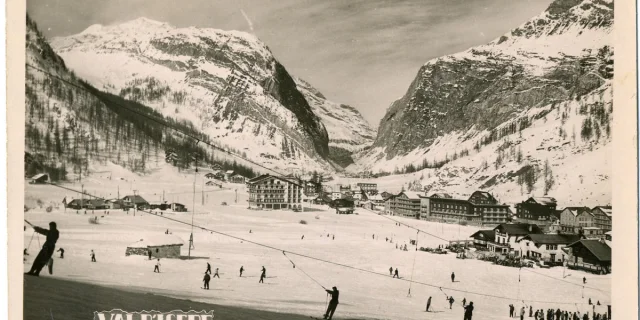

Yet when we look closely at an old photo of the tiny village of Val d’Isère, huddled around the church tower as if frozen beneath its layer of snow, we get a sense of remoteness from which a question arises.

What were they looking for, those who followed the narrow Haute Tarentaise road during the first twenty years in the resort’s history, to find at the end of their sometimes perilous journey, this village at the world’s end, flooded in dazzling light?

How many people, at that time, realised that skiing, a sport for the initiated, would become a highly popular recreational activity some forty years later?

As a child, I was out walking with my father on a summer evening at dusk, near the small St-Jean chapel by the Solaise post office. At the time, I was barely taller than the flowering grasses just before the hay harvest.

Suddenly, my father stopped, took my hand and, scanning the mountain summits that to me seemed unconquerable, leaned over as if to tell me a secret and said ‘How beautiful this land is, look at Bellevarde’s terraces sloping down towards us. When you’re a bit older, a miracle will happen. In five minutes, hey presto, you’ll be at the top, then you’ll schuss down and off you’ll go back up again! One day you’ll ski down all of these mountains, and so will other skiers from all over the world!’

Adding actions to his words, he took an athletic stance and mimed taking flight for the nearby peaks. ‘And champions from every nation will come to compete here, right where we’re standing now.’

I looked at the pastorally peaceful slopes and the summits that stood out against the bright twilight sky.

I was dismayed. My father had lost his mind!

And yet… He seemed so convinced of the reality of these impossible feats that, without even realising it, I was already contaminated by his enthusiasm.

That was in 1935.”